“I’m so sorry, but the results came back and unfortunately, it’s cancer. We need you to come back in right away.” I don’t remember anything else from that phone call, but those words are etched in my memory. In that instant, my life was forever changed by a diagnosis of aggressive triple negative breast cancer. This uncommon type of breast cancer grows rapidly, recurs frequently, and responds poorly to treatments. I was only 28 years old.

Fortunately, we caught my cancer early. I had an outstanding care team and was surrounded by a supportive community that helped me through the hardest parts of my journey. After six grueling months and two chemotherapy regimens, I underwent major surgery to remove the cancerous tissues. When I woke up, my doctor told me the treatment worked and they couldn’t find any remaining tumor. It’s hard to find words to describe how I felt when I learned I had “no evidence of disease,” (the phase many survivors prefer to “cured”), but that was the moment I dedicated my career to giving that feeling to other cancer patients.

Pivoting to Translational Research

I pivoted my career from infectious disease research to cancer immunotherapy after completing my PhD training in the Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology program at the University of Minnesota. Immunotherapy works to boost a patient’s immune system to recognize and kill their cancer. These approaches work incredibly well for some patients, but many patients have tumors that do not respond to current immune-targeting treatments. I resolved to change that. I shifted my focus from “basic” or “foundational” research, which asks questions about the world around us, to “translational” research, which prioritizes bringing laboratory findings into the clinic to help patients. I moved across the country to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and University of Washington for postdoctoral training. I learned from experts in cancer biology, cancer immunology, T cell engineering, and clinical trials. Then, in 2023, I moved to the University of Virginia to lead my own cancer immunology research program. My ultimate goal is to develop immunotherapies for difficult-to-treat cancers so other patients can feel how I did when they are declared free of disease.

Funding Cancer Research

As a lab leader, my patient experiences directly influence my work. I have a much greater appreciation for the process of bringing new medicines to patients. During treatment, I was given three common chemotherapies. I also have a BRCA gene mutation, so I received a fourth chemotherapy specifically for BRCA-mutated tumors. The original studies leading to that specialized drug were funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) more than 30 years before my diagnosis. That early research was so promising, biotech and pharma partnerships supported the drug development and clinical trials needed for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Now, it is broadly available for cancer patients. Knowing this research pipeline is why I am alive today, I advocate strongly for robust, sustained and predictable federal research funding. I also seek out industry partnerships to get therapies my lab develops to the clinic.

Centering the Patient Experience

After receiving cancer treatment, I deeply consider how our work could positively and negatively impact patients. We are trying to create new medicines to control tumor growth and prolong survival, but these medicines are only helpful if any side effects are manageable. Thinking about patient concerns is not unique to my research group, but this mindset helps me prioritize research directions that center patient perspectives. My experience has also inspired me to engage research advocates, who are often current or former patients, in our work. People who have experienced a disease have a unique and valuable perspective to offer researchers, even without formal scientific training. I meet with these advocates regularly, discuss our work, and listen to their feedback. Advocate input has helped us to modify clinical trials and interface with people who could benefit from these new therapies. Their input has helped us design better early-stage experiments and communicate insights from our work with the public. Scientists don’t need to personally experience a disease to be passionate about helping people affected by it, but my experience has taught me that collaboration between advocates and researchers has the potential to transform the impact of biomedical research.

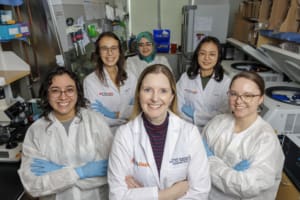

Dr. Kristin Anderson (center) with her lab trainees at the University of Virginia, October 2025

Photo Credits: Lathan Goumas