All cancer diagnoses are scary, but today many women beat breast cancer and go on to live long, healthy lives. This was not the case just a few decades ago, especially for women diagnosed with a type of breast cancer called HER2-positive. However, thanks to discoveries in immunology, we now have treatments for HER2-positive breast cancer that mean women with this diagnosis have the highest survival rate of all breast cancer types. According to UCLA Health, as many as three million lives have been saved since these treatments were developed.

This is the story of Herceptin, an immunotherapy whose discovery illustrates how researchers in different fields, working on different things, build off of each other’s discoveries to make new treatments that dramatically improve patients’ lives.

Most people with cancer will be treated with chemotherapy, which delivers a cocktail of toxic chemicals to damage anything fast-growing, like cancer cells. However, doctors are always searching for a way to kill cancer cells with fewer bad effects on the rest of the body. Our immune system has very precise ways to find and kill bacteria and viruses using antibodies, but could antibodies be harnessed to fight cancer?

Uncovering HER2

The first key discovery on the way to Herceptin came in 1984 when researchers noticed that rat tumors had extra copies of the gene we now call HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2). Later, a different group looked at thousands of human tissue samples to measure how much HER2 was present in tumors, and if there was any correlation with patient survival. They saw a clear pattern, patients whose tumors had higher levels of HER2 survived less time after their diagnosis. Still, no one knew why.

The answer came from researchers who were trying to understand why breast tumors kept growing when healthy breast tissue didn’t. They discovered that HER2 acted like a gas pedal: when pressed, it drives the tumor to grow uncontrollably. The more HER2 there is, the more the gas pedal is pushed, and the more the tumor grows. This insight opened the possibility of a way to stop the growth of breast cancer: could scientists find a way to put the brakes on HER2? To do so, they needed a way to locate and block HER2 in the tumor.

Enter the Immunologists

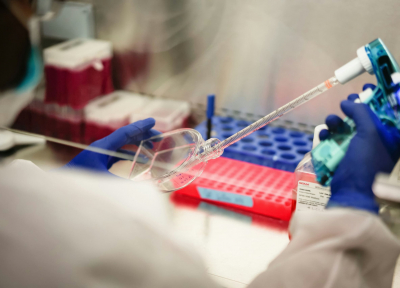

In 1975 immunologists discovered how to make unlimited amounts on an antibody that targets one specific thing. Think of it like finding the exact key for a lock, then being able to manufacture endless copies of that key. These “antibody keys,” called monoclonal antibodies, detect one thing, and they do it very well. Breast cancer researchers realized that if they could create a monoclonal “antibody key” to fit the HER2 “lock”, they could shut it down and stop tumor growth. As a bonus, monoclonal antibodies to HER2 also tag the tumor, helping the immune system recognize it and ramp up its attack. One breast cancer researcher, Dr. Dennis Salmon, brought this idea to Genentech, and from that collaboration came the drug Herceptin.

Herceptin, also known as trastuzumab, was tested in four clinical trials that included over 10,000 patients where treatment with the immunotherapy along with standard chemotherapy extended the overall life of patients, and how long they stayed free of disease. At first Herceptin was only approved to treat metastatic disease, breast cancer that has already spread to other parts of the body, but it was so successful that it was expanded for use in early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer, and even for HER2-positive stomach cancers.

Refining and Improving

Some pharmaceutical companies have now developed what are called antibody-drug conjugates or ADC using Herceptin. These take advantage of Herceptin’s ability to seek out the cancer cells and block HER2 activity but also deliver the chemotherapy directly to the cancer cells reducing the bad effects of chemotherapy on the rest of the body. However, even Herceptin has limitations because not all patients respond to the treatment.

Herceptin is a success story built on the work of oncologists, cancer researchers, biologists, and immunologists–each contributing from their own area of expertise. The breakthrough discovery of monoclonal antibodies opened the door to many of today’s antibody-based immunotherapies and highlights how research that seems basic, with no obvious application, can unexpectedly lead to groundbreaking advances in medicine.