The heart leaves one’s body as the monitors fall silent. A life has ended — but hope is born, and a gift is about to begin for another.

In another room, miles away, a patient lies waiting. Their heart is failing. Their skin pale, their breathing shallow. Every beat, a struggle. Families pray, nurses whisper, a surgeon checks the clock.

The heart arrives — still warm and preserved on ice — and the atmosphere in the operating room changes. Everyone knows what’s at stake. The heart, which once carried the rhythm of laughter and love, is being asked to give somebody another chance at everyday life.

The surgeon connects the vessels stitch by stitch. Blood fills the chambers. The monitor flickers. Then it happens — one strong beat. Then another.

A new rhythm. A second chance.

When the Miracle Meets the Immune System

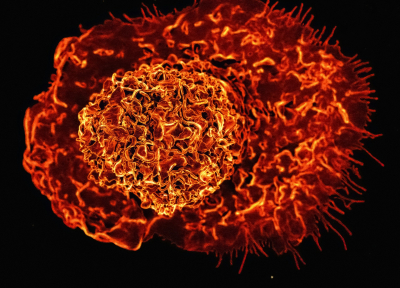

This is the story of every transplantation. But that story doesn’t end in the operating room. Every cell in your body carries a set of molecular “passports” that say: “I belong here”. When a new organ enters the body, it brings a passport from a different place. To the immune system, that looks suspicious. And so, just as the patient begins to heal, the immune army awakens — T cells, macrophages, and monocytes flood the scene, ready to defend. They do not realize that this “intruder” is the very thing keeping their host alive. It’s the most tragic misunderstanding in medicine — the body rejecting the gift meant to save it.

The Immune Response

The immune system is nature’s most vigilant guard. Its job is to know what’s self and what’s foreign. In transplantation, that distinction blurs. When the donor heart is deprived of blood and then suddenly reperfused (restored blood flow), the oxygen in the blood triggers inflammation known as Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury (IRI). This activates innate immune cells — especially neutrophils and monocytes — which release chemical distress signals (cytokines). These early responses can set the stage for organ transplant rejection.

Once the innate alarm sounds, T cells, part of the adaptive immune response, take over. The T cells recognize the donor heart carries a foreign passport and mount a targeted attack — the hallmark of acute rejection.

To prevent this, transplant patients take immunosuppressive drugs. These medicines save lives but also weaken the patient’s defenses against infection and cancer. The future lies in tailoring therapy — finding each patient’s immune balance so the organ is protected without silencing the body’s resilience to other threats. It’s like turning down the city’s alarm system to avoid false alerts, knowing it might also let danger slip in.

Teaching the Immune System to Accept

The ultimate goal is immune tolerance: guiding immune cells to recognize a new heart as part of “self.” In our work, we study how different types of immune cells called monocytes and macrophages influence this process. By decoding their behavior after IRI and during recovery, we hope to uncover new ways to prevent rejection before it begins.

Most people see transplantation as a surgical triumph. But for me, as a surgeon and scientist, the most profound moments happen in the lab. Every experiment we do, every dataset we analyze, every image we take— across a range of cutting-edge immunology techniques — tells part of that story: how the immune system decides to accept or reject an organ transplant.

Every Heartbeat a Legacy

Every heartbeat after transplant carries the legacy of two people: one who gave, one who received. And understanding immunology is how we are trying to make sure that connection withstands.

Transplantation is not just a medical procedure — it’s a story of generosity, loss, and science woven together. Immunology helps that story continue. It teaches us to guide the immune system gently — not with force, but with understanding — until it sees that a new heart is not an enemy, but a gift.

Author Bio:

Bilal Khan Mohammed, MBBS, MD, is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Cardiac Surgery and Transplant Immunology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. His research explores immune mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), monocyte–macrophage signaling, and strategies to prevent graft rejection through immune modulation and tolerance.